For Marcia Brodie, dementia caregiving was never theoretical.

Nearly two decades ago, both of her parents developed cognitive impairment — one with vascular dementia, the other with Lewy body dementia.

Brodie moved back home to help care for them, learning through trial and error how quickly everyday interactions could become confusing, exhausting and emotionally charged.

“What literally is happening is the brain is shrinking,” Brodie said. “Language skills often go first, and communication can become very, very difficult.”

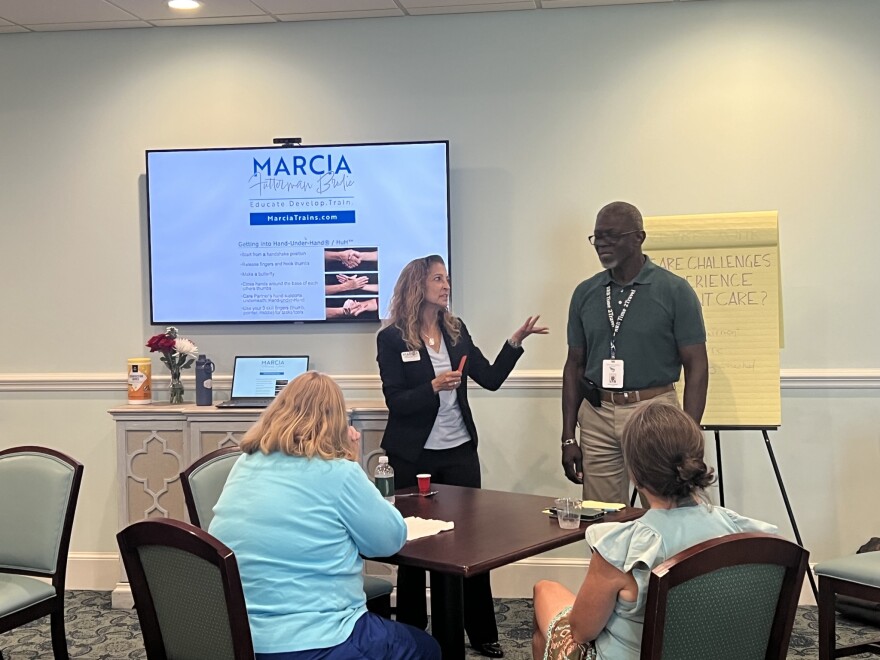

After her parents died, Brodie went on to work in senior living and eventually became an Alzheimer’s support group facilitator. Today, she runs her own business in Norfolk as a dementia caregiver educator, teaching families and care staff how to communicate with people whose brains no longer process language the same way.

Brodie said when caregivers rely on verbal explanation alone, frustration builds on both sides. That stress can escalate behaviors, overwhelm families and make home care feel unmanageable.

She encouraged families to rely more on body language, tone and simplified cues — and to avoid correcting mistakes that could cause embarrassment or agitation.

“The most important thing is to try to find joy wherever you can with that person, because it's really difficult for the caregiver, incredibly stressful,” Brodie said. “And you don't want that person who's living with this disease to be in a stressful environment.”

Care for family members with dementia is often expensive.

Hiring in-home help could cost between $35 and $45 an hour, and living in a senior community can take $7,000 to $10,000 a month, Brodie said.

Medicare does not cover long-term dementia care, and many families Brodie saw did not have long-term care insurance.

“A lot of people end up doing it on their own because they can't afford to send them somewhere and they don't have long term care insurance,” Brodie said.

For David Phillips, being the sole caregiver of his 71-year-old husband who was diagnosed with dementia has been an uneven and unpredictable journey. His husband remains physically mobile and can still dress and feed himself, but changes in behavior have become more frequent.

“It grows a little bit more difficult every day,” he said. “I never know what to expect.”

He now handles nearly all of the household responsibilities such as finances, cooking and daily logistics.

Although the couple is financially stable for now, Phillips said the uncertainty is always present.

“I think about it almost every day,” Phillips said. “If he needed 24-hour professional care, I’m just not sure what we would do.”

Brodie said learning how to communicate more effectively cannot eliminate the cost of care — but it can reduce stress, prevent escalation and sometimes help families feel more capable of keeping loved ones at home longer.

When caregiving becomes physically exhausting or isolating, Brodie encourages families to look for outside help through part-time in-home support, trusted community members or respite care.