Six months after opening Pagoda Ice Cream, owner Matt Henry hung a sign on the door: “We’ll be open no longer. Why? IYKYK.”

Those last five letters stand for “if you know, you know.”

Henry said it’s well-known in the local community that businesses never last long at the Pagoda, the centerpiece of a carefully manicured garden located in Norfolk’s Freemason neighborhood.

Since 2014, at least five full-time businesses have operated in the space, all closing within a year. Though the location hosts pop-ups and events, it has sometimes sat without a full-time tenant for a year or more, leaving residents to wonder what happened or what’s coming next.

Three former business owners told WHRO that it’s not the city’s business climate, or the low season, or a desire to move on that drives businesses out of the Pagoda.

They pointed the finger at one person: Madeline Sly, who since the late 1990s has run the foundation that leases out the property.

Former business owners say she interfered with operations and dictated where they could move furniture, what artwork decorated the walls and, ultimately, their success. They say her overbearing approach has harmed what should be a crown jewel for the city.

Sly says she simply has high standards for the Pagoda, which she’s made her life’s work, and many businesses just don’t have what it takes to survive.

A revolving door of businesses

Mike Evans has lived in Freemason since 1988. He said the Pagoda has been a point of controversy among neighbors. Some want the garden to stay quiet with no people, while others want it to be active. He said he never understood why businesses didn’t stay long.

“It’s always been kind of a mystery and a disappointment to me that somebody didn't pull it off,” Evans said, adding he’s always wanted to see a coffee shop that serves breakfast sandwiches in the space.

After Henry’s cryptic announcement about Pagoda Ice Cream, people posted a flurry of their own theories on social media. Some Reddit users wondered if the place is “cursed.” Others said relationships between business owners and The Friends of the Pagoda and Oriental Garden Foundation, which manages the property, quickly turn sour.

The foundation’s president, Madeline Sly suggested things don’t last because the business owners want to move on or lack the acumen to survive winter, when foot traffic drops at the out-of-the-way location. But past business owners said unreasonable restrictions and Sly's heavy-handed management made running a business in the space unsustainable.

“No one expects to go into a space, spending that kind of money as a business owner, to close within a year,” said Kisha Moore, who opened Hummingbird Macarons at the Pagoda Garden and Teahouse in early 2019 and closed by February 2020, unrelated to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The city of Norfolk owns the Pagoda and the Japanese garden that wraps around it. The Friends of the Pagoda Foundation leases the site for $1 a year. In exchange, the foundation maintains the garden and building, and has since the foundation was founded in 1998. The agreement saves taxpayers an estimated $250,000 a year, according to WAVY.

The city doesn’t track sub-lease activity outside of making sure each business follows zoning requirements and insurance obligations, the city’s director of real estate Wayne Green wrote in an email. The arrangement is similar to the one the city has with Selden Market, said Mia Byrd Wilson with the city’s Department of Economic Development.

In the case of the Pagoda, Julie Aubrey, owner of Mermaid Catering, said the lack of oversight from the city is a “waste.”

“It could be a huge benefit to downtown Norfolk," she said.

Aubrey took over The Pagoda restaurant in 2014 and left in 2015. The Pagoda restaurant reopened in 2017 under Ted Papafil, owner of Norfolk Catering Company and Norfolk Grille. Classically-trained pastry chef Kisha Moore ran her macaron and tea shop from 2019 to 2020. Chocollage Bakery and Cafe at the Pagoda opened in July 2023 and closed that October, Sly told WHRO. Pagoda Ice Cream opened and closed in 2025.

“I don't think that anybody is going to be successful as long as the foundation is managing the restaurant portion of it,” Aubrey said.

Tensions

Restrictions ranged from not being able to change table layouts and rearranging furniture, to not being able to change decor or the style of dishes and glassware, Aubrey said, far beyond the kinds of rules most landlords impose on business tenants. The restrictions became an issue when trying to attract new customers.

“They would love the food, and they would love the service, but the inside of it was so dated that it just really wasn't attractive, especially to a younger crowd, to make it a regular hangout or a regular place that they would go to,” she said.

Not being able to take creative control of the space impeded growth, Moore of Hummingbird Macarons and Desserts said.

And Sly’s hands-on approach to enforcing those restrictions only made matters worse.

There was the “constant coming in, checking on you, making sure things weren't being moved,” Moore added.

Henry said during the few months his ice cream shop was open, Sly would check in twice a day, every day. The two immediately started butting heads.

Sly once locked one of the three doors into the ice cream shop to discourage people from using the bathroom inside, he said, adding she did this without consulting him. She also shot down his idea to bring food trucks to the area to drum up more business.

“That was the epitome of how she controlled your business,” Henry said, referring to the food truck conflict. He noted interactions often overstepped the bounds of a standard landlord-renter relationship.

But Sly said the relationship isn’t actually that of a landlord and renter. The businesses that come into the space don’t sign a lease, but rather a management agreement, she said.

They're running the business through the foundation, Sly said.

But in practice, this arrangement creates confusion for the business and a disconnect for customers, Moore said. Someone needs to be able to sign a “real lease” that gives them creative control over the inside, or the foundation needs to hire someone to manage a restaurant under their footprint, rather than under the guise of a “new business,” Moore said.

“You can't have two ideas, two brands in one space,” she said.

The arrangement comes with restrictions. They can’t move “artifacts” or furniture, they can’t redecorate, and they have to work their schedules around events like weddings and parties, she said.

Sly says businesses set their own menus and hours — something previous operators dispute.

“I don't back down on the fact that I do have high standards here,” Sly said.

Sly said she expects people to fit their business to the Pagoda — not the other way around.

Aubrey said she decided to leave the Pagoda after a year because she didn’t think the business would survive another winter with the restrictions.

“I think they treat it like their charity clubhouse, not like it's something that is a viable, serious business venture for the person who's going in there and taking those risks,” Aubrey said.

She said Sly wouldn't let her scale back the menu or cut store hours in the slow season. Aubrey said in the winter, this translated to wasted time, food and lost revenue — an estimated $20,000 a month from mid-October to the beginning of March.

A ‘unique treasure’

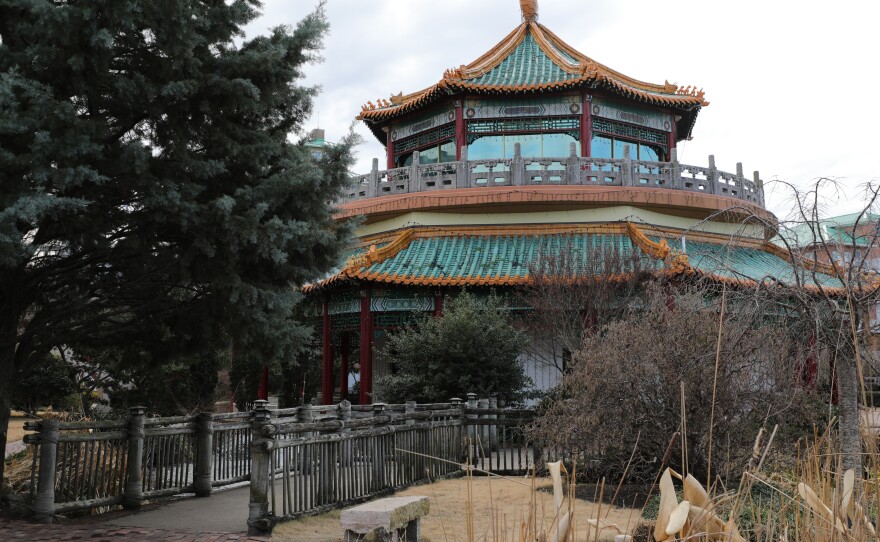

Walking through the Freemason neighborhood in Norfolk, the Pagoda is somewhat unexpected.

The saturated reds, blues and oranges of its exterior stand out against the backdrop of the otherwise drab buildings of downtown. Ornamental dragons encircle the roof and overlook the grounds. A path meanders around the structure, through a garden, over a koi pond and past three doorways: the gate of Norfolk’s blessing, gate of the moon and gate of the morning sun.

Inside, an elevator and spiral staircase takes people to a second floor. The balcony offers a panoramic view of downtown, the USS Wisconsin and the Elizabeth River.

“People love to come here and just meditate,” Sly said. “A lot of people working downtown will come over for just a little respite during the day.”

That wasn’t always the case. Sly remembers when the site was a 500,000 gallon molasses storage tank surrounded by concrete.

“We used to live in West Ghent, and we would ride our bikes down and tie them up at the molasses tank and go to Harbor Fest,” she said.

The Taiwanese government built the Pagoda, also called the Marine Observation Tower, in 1989 as a symbol of trade relations. But the city didn’t have the funds to manage it, Sly said. She watched it fall into disrepair in the years that followed.

In 1998, she spearheaded The Friends of the Pagoda and Oriental Garden Foundation, formed by members of the Freemason Street Area Association and the United Chinese-American Association. Sly, then co-president, led the effort to raise the funds to repair and enclose the building. The foundation hired Chinese artisans to redo artwork and installed a garden. Sly said she hand-selected thousands of plants and envisioned a garden with a surprise “around every turn.”

“The vision was to create something special that people would enjoy,” she said. “It just took a lot of work and effort to bring people together to make this happen.”

Sly said the Pagoda is an art gallery, museum, event venue and restaurant. Traditional East Asian brush paintings adorn the walls. A large statue of Buddha sits under the staircase. Upstairs, lotus chandeliers and a traditional Taiwanese lantern hang from the ceiling. Cabinets display Chinese porcelain and other artifacts.

“It all has a story,” she said. “It's all beautiful.”

The foundation doesn’t seek out businesses to manage the space, but has been willing to give entrepreneurs an opportunity, Sly said.

The space has been hosting Dreal's Creole Southern Soul on Friday evenings since 2020. The weekly event is enough, Sly said, repeatedly expressing she dislikes the term “pop-up.”

“That's about as full time as I want,” she said. “I'm not looking for somebody full time.”

‘It's all in her hands’

Sly, community members and business owners agree that the Pagoda is special. But that’s where the agreement stops.

Business owners say her preservationist attitude stifles their ability to run an effective business.

Moore said the foundation does a great job with the garden, but inside should be allowed to evolve to realize its full potential.

“The foundation has a sense that they own the space, and that sense of ownership, it keeps people from being able to flourish in the space,” she said.

Kate Villaflor, a Norfolk resident who helped Henry at Pagoda Ice Cream, said the Pagoda should be open for people to enjoy.

“When there's no business in there, that place is locked up,” she said. “Nobody can go in.”

Henry said the foundation seems to be a one-woman show.

The foundation’s website lists three members, including Sly, who’s been president since 2003. WHRO confirmed that one of the still-listed members on the website died in 2018. The foundation’s 2025 annual report to the State Corporation Commission lists seven active board members and doesn’t include the deceased member. Sly said the board meets on an as-needed basis.

Henry said the only member he ever interacted with was Sly. He said he hopes the city re-evaluates the arrangement.

“The businesses are either leaving or failing,” he said. “Why is that? Why are they failing? Why are they leaving? And there are obviously different opinions to that, but there are some common elements here.”

Sly said the reason some didn’t last was because the Pagoda is seasonal. Others, she said, simply wanted to move on.

Prior operators say that's not the case.

Moore said she was concerned her relationship with the foundation wouldn’t remain positive if she stayed longer than a year. Henry said he decided to close his business after the relationship with Sly deteriorated. Aubrey cited the unsustainable revenue losses caused by Sly's restrictions.

At times, it seemed that Sly didn’t want Pagoda Ice Cream to succeed long-term, Villaflor said, noting small interactions that often turned petty, like the micromanaging staff and taking away an oscillating fan staff used on hotter days.

“I don't think it mattered to her that somebody's livelihood is counting on, basically, her and it's all in her hands,” she said.