Democracy at Work is an election-season series from VCIJ at WHRO. People share stories about how they upheld the core ideals of American democracy.

Anne Adams drove her 27-year-old Mazda over the gently rolling hills of Highland County, Virginia, a faded but prominent “Press” sticker glued to the front windshield.

She passed farms, bright white churches and the occasional sugar shack— for which the region is well known for making maple syrup – on her way to the day’s assignment.

Adams – owner, publisher, reporter and photographer for The Recorder – arrived to cover a memorial for a local woman whose remains were recently found 51 years after she went missing. As she has done thousands of times before, Adams would bring to light a small, new and important story for her community.

“What I just learned early on was the newspaper, in a place this small, you can have a very positive effect,” Adams said. “Once you realize how critical that is, then it just motivates you.”

For more than 30 years, Adams and her weekly newspaper have been a herald to the residents of Highland, Bath, and, now, Alleghany counties. The Recorder, covering a region with a population just around 22,000 and an area larger than the state of Rhode Island, has been continuously published since oxen first pulled the paper’s printing press into the county seat of Monterey in October of 1877.

Adams, 56, has preserved an historic institution under constant economic threats in recent decades, due to the decline in print advertising and the dominance of tech companies in digital marketing. More than 40 papers in Virginia have shuttered in the last 15 years and seven counties have no newspaper reporting in their communities, according to research by Penelope Abernathy, Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics at the University of North Carolina.

The Recorder serves an isolated community, nestled in the Allegheny mountains along the border with West Virginia. The region sits a little over an hour away from where founding father’s Thomas Jefferson and James Madison called home—where the first amendment and the concept of freedom of the press was born.

Jefferson thought new laws drafted during the Constitutional Convention were missing a key ingredient that would be essential to a representative democracy, one that could be trusted by the people. Jefferson wrote that “our liberty depends on the freedom of the press.”

On Dec. 15, 1791, Virginia became the 10th state to ratify the Bill of Rights, and with it, the First Amendment guarantee to freedom of the press.

“They knew it back then. If you don't have a free press, if you don't have good, experienced, journalists willing to do a lot of work, spending a lot of time making sure that the right information is published where everybody can see it,” Adams said, “Then you're going to end up with an ignorant population because folks wouldn’t do that kind of work on their own, would they?”

When Adams graduated from Tulane in 1990 with a BFA in art, a journalism career wasn’t even a blip on her radar.

After college, she followed her mother to Highland County to help renovate her home. She fell in love with the natural beauty of the landscape and wanted to stay but needed a job. She applied for an opening at one of the largest employers in the town, The Recorder. That year, the weekly had 17 employees.

Adams was hired and started out selling advertisements. She quickly advanced to typesetting, writing features, bookkeeping, accounting and even helping run the cranky printing press. Eventually, Adams became the general manager and fell more deeply in love with the community she was reporting on.

“You have this experience of ‘What can I do to make a real difference?’ That’s meaningful work. And, no, you don’t make money, but it's meaningful work,” Adams said. “I can look back on 35 years. I did some good. I did right for the people.”

In 2007, as the banking collapse was beginning and the great recession looming, The Recorder’s publisher, Lee Campbell, like many of his contemporaries, was ready to sell the paper and retire.

Adams didn’t want to see her newspaper shuttered or bought by a cost-cutting hedge fund. After more than a year of negotiations with Campbell, she bought the paper.

The horizon, however, was dark and she found herself steering her new business through one of the most turbulent economic times since the depression.

“How can we continue to afford to create the product without sacrificing quality and coverage?” she wondered. At first they cut pages and columnists, decreased use of color and increased their newsstand price to $2, the highest for a weekly paper in the state.

After struggling for a decade to make ends meet, she and her staff sat for a hard talk about the road ahead. “We're sick of fighting for cash, sick of being so poor. So we did something very dramatic. We weren't sure if it was going to work. We more than doubled our subscription price because we said the readers ought to be picking up more of this tab.”

In 2018, Adams increased the annual subscription price to $99, a fee that matched The Washington Post at the time.

“But if we're going to do that, we’ve got to give them something worth paying for, really a better product,” she said. Adams set a minimum number of pages to 40, increased color printing, and brought back cherished columnists. The weekly began to publish on high-quality, bright, white paper stock.

“It was pretty, really pretty. We had very few complaints and people really liked it. Our financial picture improved to where we weren’t having to pinch every penny.”

But just as things were starting to brighten the Covid pandemic hit. Advertising revenue dried up. “I don’t know how papers made it through,” she said. Many didn’t. “I was terrified.”

“So, I wrote a plea to my readers: ‘April is going to be our last edition unless you help us out. Help us help you.’ Because that was right at the time when folks needed us more than ever. We were reporting 24/7. It was nonstop coverage.”

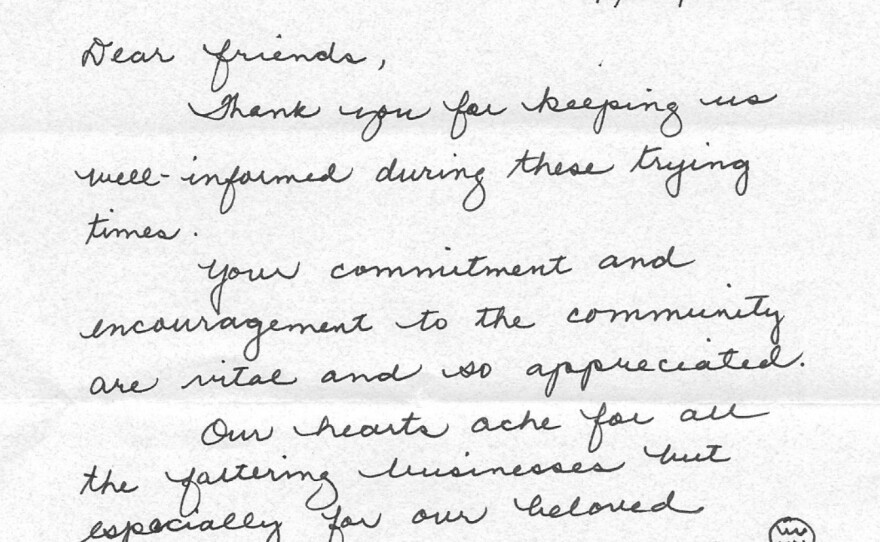

Adams innovated. She appealed to readers to purchase advertisements for their local businesses, an idea that went over so well that it is still in play today. Some readers donated money and sent encouraging letters despite the paper being a for-profit business.

“It was emotional every day opening up and reading these notes. and I felt like I got really close to my readers,” she said.

“I have seen communities who've lost their paper,” she said. “I'll be damned if that's going to happen here, if I can help it. We've met up against some stuff in this region that could have changed the environment, the quality of life forever.”

Over the mountains from Bath County, a newspaper in Covington, Virginia, that served Alleghany County for more than a century, had recently been sold and the new owner had fired a majority of the paper’s senior staff. Adams saw an opportunity to expand. She rehired those journalists and sent them back out on their old beats.

“I want to help my community. I've seen how much good we can do. I've seen how much good information we can get out there to folks, to help people with issues. It is such a privilege to tell stories about the people here.”

Reach Christopher Tyree at Christopher.Tyree@vcij.org