Waters are rising more quickly in Southeastern Virginia than almost anywhere else in the country, and scientists have long known that sinking land is a major reason why.

A new study led by Virginia Tech helps pinpoint exactly how much. Researchers found Hampton Roads is sinking an average of 2.3 millimeters per year.

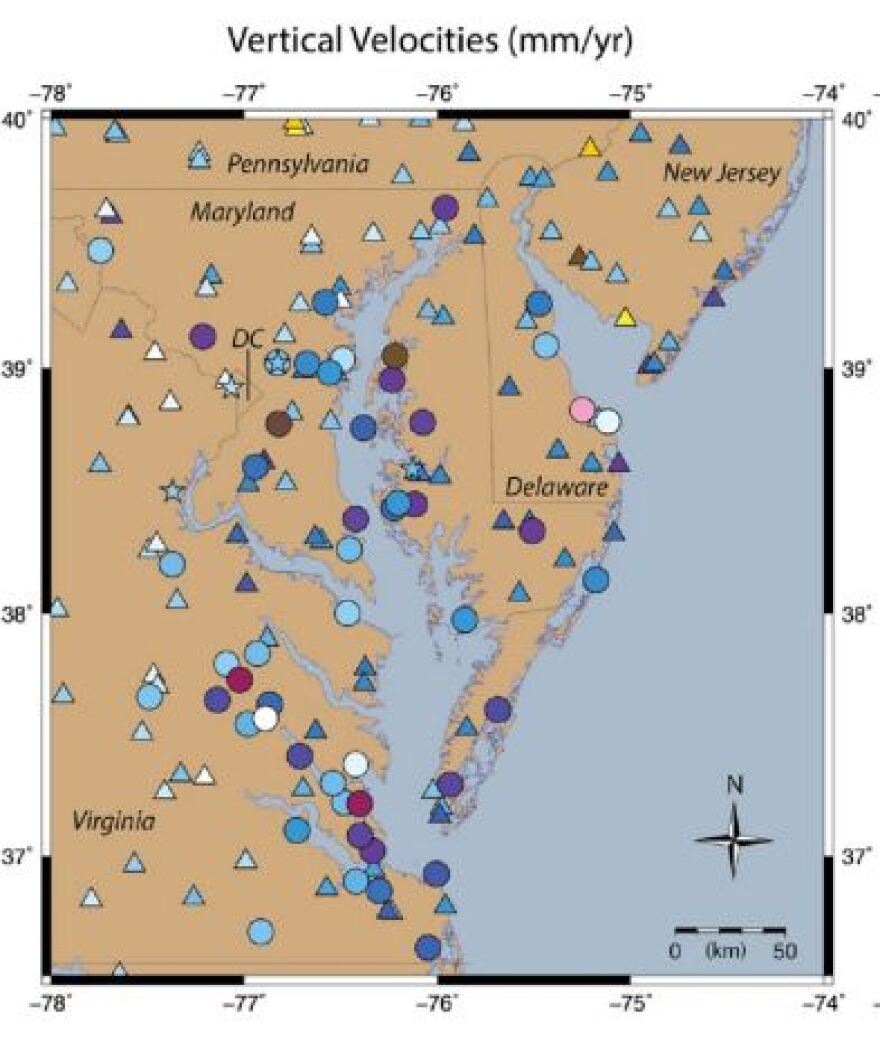

The effort, a collaboration between several universities and government agencies, provides the most detailed picture yet of land subsidence, or sinking, across the Chesapeake Bay.

Scientists and officials are trying to understand the issue as climate change raises sea levels, which compounds the problem and threatens infrastructure in coastal communities.

Sarah Stamps, an associate professor of geophysics at Virginia Tech, said the group homed in on the Chesapeake Bay because it’s known for subsidence and sea level rise on the East Coast and has immense economic value.

People in the region were “very interested” to learn how land levels changed since research done a half-century ago, she said.

Past studies, including from Virginia Tech, have assessed subsidence rates across the Atlantic coast, confirming the bay area as particularly vulnerable.

The recent venture, which included work by Hampton University, the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Geodetic Survey, dove deeper to get more detailed data throughout the region, Stamps said.

The team gathered information between 2019 and 2023 at 175 sites, including about two dozen in Hampton Roads, Western Tidewater and the Eastern Shore. Some were measured each year, while others are permanent, continuous monitoring stations.

To determine the land’s exact position, on-site researchers used high-precision instruments to capture radio signals transmitted from satellites orbiting Earth more than 12,000 miles from its surface, Stamps said.

Subsidence was "ubiquitous” across the bay region, researchers found, ranging from nearly 3 millimeters to less than one. A handful of spots experienced uplift, where land rose rather than sank.

The rate of subsidence, however, has seemingly slowed since the 1970s assessment. That’s likely because of changes to policies about pumping groundwater, Stamps said.

Most sinking is because of natural geological forces. More than 10,000 years ago, during the last ice age, parts of North America were covered by massive ice sheets. After they melted, the ground has been slowly adjusting to the retreat of all that ice.

There’s nothing humans can do to stop that process. But other factors contribute to subsidence, such as centuries of drawing groundwater and potentially the movement of sediment around the bay.

A few millimeters may sound trivial, but they will help shape the long-term impacts of sea level rise. Scientists focus on “relative” sea level rise, which accounts for land sinking and the amount of water that rises.

“You have to combine both the effects of the changes in the sea level with the changes in the land,” Stamps said. “If the land is moving down and the sea level is moving up, then the shoreline is really going to be moving inland further. So when that happens, the impact of flooding is more substantial.”

Her team is now working to decipher how much land is sinking from each cause, such as changes to the sprawling Potomac aquifer.

That includes drawing information from the U.S. Geological Survey’s network of extensometers, including one at West Point on the Middle Peninsula. The devices extend more than 1,000 feet underground to measure land motion in the aquifer.

Stamps said they have used additional technologies at the extensometer sites, such as ground-penetrating radar and magnetics.

The data is accessible through an online repository. Stamps said the goal is to help leaders consider subsidence when making decisions with long-lasting consequences.