The country’s largest power grid operator, which helps manage electricity in Virginia and across the mid-Atlantic, is continuing to see record-high energy prices.

The organization, PJM Interconnection, oversees 13 states and Washington, D.C. This week, it announced the results of an auction that helps determine the upcoming energy needs of its massive service area, which includes more than 67 million people.

Electricity prices soared to a record high, fueled by skyrocketing demand from data centers and extensive delays in getting new energy projects online.

Leaders across the region are growing increasingly frustrated. Nine governors, including Virginia’s Glenn Youngkin, recently sent a letter to PJM voicing concerns.

“With billions of ratepayer dollars and the stability of our grid at stake, it is critical that PJM take concerted, effective action to restore state and stakeholder confidence,” the governors wrote.

Here’s what you need to know.

What is PJM, and why does it matter?

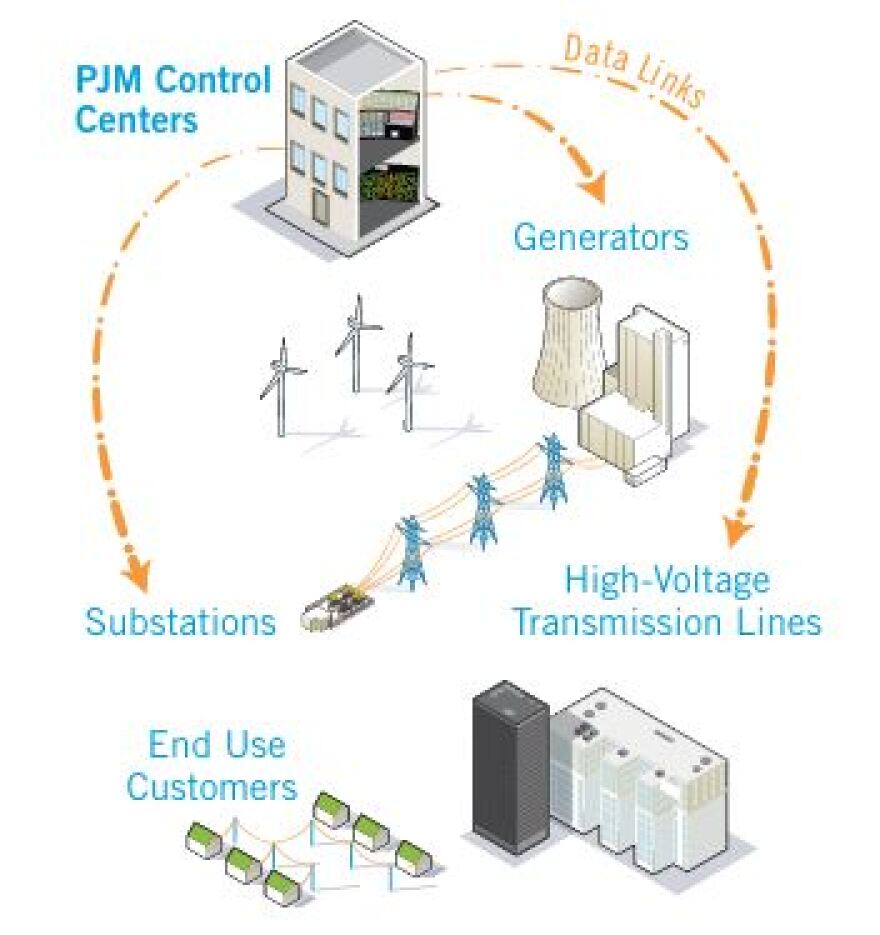

PJM is a regional transmission organization, or RTO, designed to keep the region’s power supply consistent and affordable.

“They consider themselves like air traffic control for electricity,” said Claire Lang-Ree, a sustainable energy advocate with the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council.

That includes predicting supply and demand, and coordinating how electricity flows through transmission lines, she said.

PJM does not own power infrastructure or profit from the sale of electricity, but includes governing members that do, such as utility companies, as well as other stakeholders including consumer advocates and power marketers.

About 60% of the U.S. electric power supply is managed by RTOs, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

This week, PJM wrapped up a capacity auction to determine how the region will meet its energy needs between June 2026 and May 2027.

The organization starts by calculating how much electricity it needs as backup during peak demand, such as the hottest and coldest days of the year.

Power operators, including Dominion Energy, then submit bids demonstrating the amount of energy they could supply in case of emergencies. These bids include a per-megawatt price: The lowest that the businesses are willing to accept while maintaining operations.

“The concept of the capacity auction is paying plants for the promise of delivering during an extreme event,” Lang-Ree said.

PJM stacks up the bids in cost order and picks the cheapest ones until hitting the necessary capacity. The more energy capacity is offered, the less PJM has to pay.

Think of it like a graph displaying supply and demand curves, Lang-Ree said. The intersection of the two lines sets the “clearing price.” That price is then paid to all of the qualifying power plants.

Over the past decade, the per-megawatt clearing price fluctuated from around $30 to $160, until soaring to a record high of $269 last year.

The trend continued this week, with the clearing price rising another 22% to $329.

Lang-Ree said there’s reason to believe it could’ve gone higher if it weren’t for a recent legal settlement out of Pennsylvania, which set a temporary price cap.

The rising costs directly affect residents’ energy bills, though they vary by state. Some states last year saw monthly bill increases of up to $30 passed onto consumers, Lang-Ree said.

In Virginia, Dominion customers are largely shielded from sudden PJM-related cost increases.

That’s because the utility’s own plants generate most of its power, making it less reliant on the regional market, said spokesperson Aaron Ruby.

“Second, we sell power generation into the capacity market, which helps offset price impacts from what we purchase,” Ruby said in an email.

Dominion customers currently pay $2 per month for their participation in the PJM auction.

Lang-Ree said the explosive growth of power-hungry data centers in Virginia could make Dominion more reliant on PJM in the future.

What’s driving prices so high?

One of PJM’s biggest challenges is getting new power projects connected to the electric grid.

The capacity auction is seen as a signal to the energy market, Lang-Ree said.

“It's supposed to say, ‘Hey, when the price is high, we need new supply in the region,’” she said. “We need new power plants built. And last year's auction really sent that signal strongly.”

But there are plenty of power plants already waiting in the wings, “trapped in PJM’s interconnection queue,” she said.

Before any energy facility, such as a wind farm or natural gas plant, can start sending power onto the grid, it must get PJM approval.

The organization studies each project to make sure it won’t cause problems for the network, and sometimes requires the developer to do upgrades. Dominion, for example, announced earlier this year that the cost of building its offshore wind farm in Virginia Beach jumped by nearly 10% because of network upgrades assigned by PJM.

It can take five or six years to make it through the interconnection queue, the slowest of any RTO in the U.S., Lang-Ree said.

Meanwhile, developers are facing problems with siting and permitting at the state level; sudden changes to federal energy policies, such as the loss of tax credits; and supply chain issues – all of which make it more difficult to ensure the project’s viability years after it enters the PJM queue.

“All of those things are causing sort of a perfect storm where resources are really struggling to get through and then really struggling to get built after that,” Lang-Ree.

Transitioning to cleaner energy sources has also made the process look a bit different than in the past, she said.

Rather than a few large coal and gas plants, renewable and battery storage projects tend to be smaller, with more total requests going to PJM.

NRDC, Lang-Ree’s group, and others advocate for changes that could speed up the process, such as considering projects in clusters to evaluate their net impacts on the grid and approve multiple at a time.

An uncertain future

State governments have traditionally been hands-off with PJM, Lang-Ree said.

But last year’s auction “really woke them up, because they saw that their constituents would be paying double-digit bill increases for the foreseeable future, unless they could get new energy online.”

In their recent letter, Youngkin and eight other governors called for new leadership at PJM and fundamental changes to the interconnection system.

“In the past, other regions looked to join PJM due to its many strengths,” they wrote. “Today, across the region, discussions of leaving PJM are becoming increasingly common.”

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which oversees PJM, is also taking notice.

In 2023, the commission ordered all RTOs to update and speed up the way they study interconnection requests, including using the “cluster” method.

Lang-Ree said PJM has not fully complied with that order.

“Their study timelines were almost double the amount of time that FERC required them to be.”

FERC is expected to issue another order to PJM this week in response.