Lois Boyle arrived at the Norfolk theater, pulling a rolling case and luggage on wheels. It was 90 minutes before curtain and she’s seen the production before. But she was here, with her equipment, to help others enjoy the show.

Boyle is the founder of the nonprofit Access Virginia, which provides captions for the deaf and audio for the blind at select productions across Hampton Roads.

Its work is entering a busy stretch as the theater season begins. It will be providing services, for example, at the Broadway show, “A Beautiful Noise: The Neil Diamond Musical,” on Saturday at Chrysler Hall.

Boyle started the organization after offering to help Angela Hill see her first stage play in decades. Hill has progressive hearing loss that started in childhood. She felt like “practically a hermit” because she couldn’t hear conversations around her. A marquee at Scope advertising “The Lion King” coming to Chrysler Hall in 2010 was the breaking point.

“I want to see that show,” she told her husband.

During that time, Boyle was providing CART communication or Communication Access Realtime Translation services locally, including at the church Hill attended.

“Miss Bo, do you think you could do a performance at Chrysler?” Hill asked one day.

A freelance court reporter at the time, Boyle lacked the knowledge and equipment for such an undertaking. But she wanted to help. She researched theaters in Hampton Roads and throughout the state, seeking their services for the deaf. The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., was the closest place she could find.

“I found that really disappointing,” Boyle said. “I knew that would exclude a lot of people with hearing loss from attending arts, and I wanted to make her wish come true. So, long story short, we educated a theater. They said, ‘Yes,’ and I learned.”

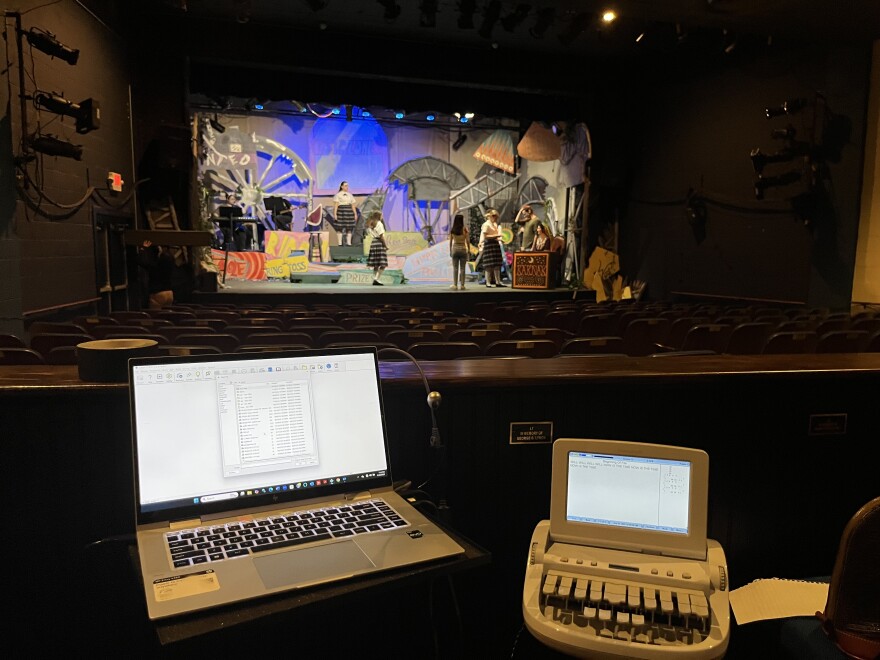

After a visit to the Kennedy Center to understand the process, Boyle set up close to a corner of the stage for one performance of “The Lion King.” While she typed in the stenograph machine she used for court recording, the words appeared on her desktop computer for Hill to read.

Boyle had set the stage for Access Virginia.

Hill was overjoyed and told her afterward, “I feel like a little girl all over again.”

“Hearing words like that drives my passion,” Boyle said. “They can laugh with everybody else or cry with everybody else because they can feel what’s happening on stage.”

Hill longed to see more shows, as did many of her peers at the Virginia Beach chapter of Hearing Loss Association of America.

Boyle didn’t have the resources to make captioning work on a larger scale. She needed an advocate and found one in Shirley Confino-Rehder, the former chair of the Norfolk, Virginia Mayor’s Commission for Persons with Disabilities. Their efforts, with support from the local Hearing Loss Association of America, led to a New York organization offering captioning services for performances at Chrysler Hall.

“I thought I was done,” Boyle said.

A year later, Chrysler reached out and asked Boyle if she could provide the captioning. Confino-Rehder suggested she start a nonprofit to be eligible for grant funding and community donations.

Access Virginia officially started in 2014. Boyle attended a mayor’s commission event where they discussed the captioning when a voice she didn’t recognize spoke up.

“What about us?” asked Frances Durham.

Durham was blind. She was born with vision but lost her sight completely when she was in her 20s. She missed the theater. And she knew others like her.

Boyle didn’t know how to help but offered to research. That led to her shadowing an audio describer, a person who verbally describes stage events for the visually impaired. In 2015, Access Virginia also began offering that service.

Audio descriptors describe the visual elements — costumes, scene changes, set design —and speak clearly into a receiver that the blind patron checks out when arriving at the theater. The receiver is so small that it can be clipped onto clothing. Earbuds are provided, though patrons can bring their own.

Just as with captioning, receiving the script in advance is as critical as attending a performance in advance.

Durham was delighted to return to the theater.

“When everybody starts laughing, now we know why they’re laughing because someone is telling us what happened,” Durham said. “We don’t have to ask somebody, ‘What’s so funny? What happened?’ ”

Durham is thrilled that Access Virginia’s expansion includes museum tours. That means when the Virginia chapter of the National Federation of the Blind hosts its state convention this fall, a trip to the Virginia Beach Aquarium will be part of the festivities, with an audio descriptor providing visual detail and information.

“That will be so exciting,” Durham said.

In addition to Chrysler Hall, Access Virginia collaborates with the Little Theatre of Norfolk, the Wells Theatre, Zeiders American Dream Theater, the Ferguson Center for the Arts, the Downing-Gross Cultural Arts Center and the Williamsburg Players. The goal is to add one theater annually.

While the theaters pay a cost, most expenses are covered through grants and sponsorships.

Boyle is applying for grants after funding cuts from President Donald Trump’s administration have already led to a decrease from one arts commission. Access Virginia does not rely on federal funding, but the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has supported the nonprofit. The significant cuts to NEA funding have resulted in the termination of grants to hundreds of art associations across the country.

Visit Access Virginia for performances where accommodations for the deaf and blind will be offered.