It’s hard to grasp the depth of the legacy Richard Singletary left, even while standing in the middle of it.

The iconic Portsmouth educator, linguist and humanitarian had a vast African art collection that filled every corner of his home, which doubled as a museum. Singletary died on June 27; he was 84.

A step inside the Singletary Gallery of African Art in the Cavalier Manor neighborhood reveals a chaos of treasures — hundreds of artifacts, paintings, pottery, tapestries, textiles, encased carvings and tribal garments filling every wall, overwhelming every nook. An unframed canvas rests against a plant in a whirlpool tub, directly inside stained glass double doors that lead to a tiny bathroom. The doors came from a Portsmouth church, just as his wooden front doors.

The eclectic collection became significant enough for Singletary, whose mastery of art and art history served multiple global organizations, to offer public tours by appointment.

“He did it his way,” said Tracy Singletary, who regards his younger brother as a Renaissance man. Tracy, 87, is here from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to tend to his brother’s affairs and all he left behind from what his brother described as a life well-lived.

Tracy only knows tidbits about the artifacts that surround him. Three weeks after Singletary's death, he’s still trying to make sense of it all; that’s easier with the personal items that include an assortment of colorful ties and many pairs of boots.

He, too, is in awe of all that surrounds him under the recessed lighting along the vaulted ceilings inside the 2,400-square-foot museum.

Masks line the walls of what would be the living room, many of which are labeled with the names of countries such as Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire and Mali. Thousands of books about Africa, art history and music pack the shelves of several tall bookcases just inside the front door. Perhaps one of the books reveals the history behind the totem pole in the adjoining room; it is tempting to touch the pole's ornate curves.

“I remember when he put this in,” Tracy said, pointing to the indoor stone fish pond with a single koi swimming.

The museum contains many instruments, including two pianos, a harpsichord, a violin, a bass violin, a cello and a French horn. The Baldwin piano in the front room is where Singletary taught lessons to young people.

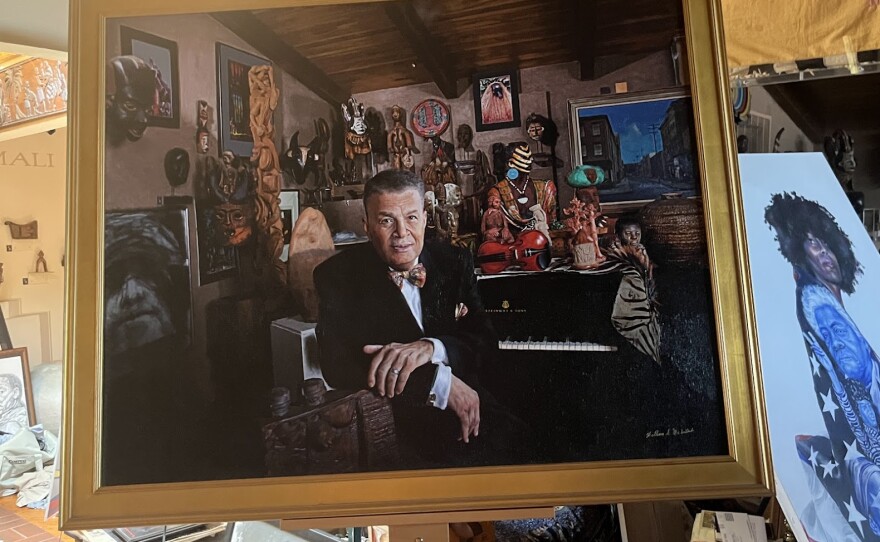

The baby grand piano isn’t as easy to spot as it’s covered with figurines from a President Barack Obama inauguration. But it clearly was a favorite piece, as that’s where you meet the gaze of Singletary in a striking portrait, snapped by the internationally acclaimed Norfolk photographer, the late William McIntosh.

Settling onto a bench on the porch, Singletary’s favorite spot, Tracy reflects on his brother, whom he said was the smartest of the three children, including middle child, Marie.

Tracy describes an idyllic upbringing in segregated Winston-Salem. Their father was a grocer, and their mother was a homemaker who dressed chickens for her husband’s store.

“It was a very unique time,” Tracy said. “Our instructors were very interested in teaching us and we had African history 365.”

Tracy completed two tours in Vietnam and his brother joined the Peace Corps, which sent him to Liberia and the Sahara region of Africa in 1964, inspiring his passion for its culture. He returned home with a handful of pieces that started his collection.

Singletary moved to Portsmouth in 1966 to teach at the former Cavalier Manor Elementary School. That marked the beginning of a long career with Portsmouth Public Schools, which adopted a program he designed to teach English as a Second Language classes. He loved languages and studied French, German, Spanish, Russian, Italian, Japanese, Chinese and numerous African dialects.

Singletary had taught himself to play piano, and, in high school, learned strings. He tutored children for more than 50 years, taking a break from 2003 through 2008 after suffering a stroke.

Many of his former fourth-grade students shared memories of him on an online tribute wall.

James Werts Jr. wrote, “He opened our eyes and minds to a world most of us only knew from televisions, magazines, and maybe books.”

Werts’ recollections include Singletary teaching the class to square dance and a Russian Cossack dance, defined by its high-energy folk style and its roots in the celebration of the Ukrainian Cossacks.

Singletary taught his students how to speak in front of an audience, preparing them for recitals. He attended a recital of one, Kesean Sparrow, at the Chrysler Museum of Art the week before his death.

Ronald Sparrow said in an interview that he contacted multiple piano studios about teaching his grandson, who has autism, when Kesean was 5 ½. All were unwilling. Then he called Singletary, who said, “Bring him over.”

Upon hearing Kesean play a few chords, Singletary took him on as a student, saying, “He’ll do just fine.”

Kesean graduated from Great Bridge High School in May and continued lessons with Singletary, who never raised his fee: $25 a month.

“I asked the good Lord to guide me, and he directed me to Dr. Richard Singletary,” Sparrow said.

JoAnne Nguyen’s nephew recently began taking music lessons. Nguyen works at Tony’s Crab & Seafood, where Singletary had eaten lunch regularly for the last 10 years, almost always ordering a whiting sandwich with a small gumbo.

“At Christmastime, he would bring the staff candy,” Nguyen said. “He was a really good person. We love him.”

Singletary wasn’t only a collector of African art. He was a scholar, earning his doctorate at Virginia Commonwealth University. His dissertation on Bruce Onobrakpeya led to a book on the Nigerian artist, commissioned by the Ford Foundation.

Singletary had master’s degrees in humanities and piano performance. He taught as an adjunct professor at Norfolk State University and Tidewater Community College.

Singletary and renowned Hampton Roads artist Charles Sibley were friends, and a side addition to the museum houses Sibley’s entire collection.

Artist Ken Wright met Singletary in the early 1970s while at the Seawall Art Show in Portsmouth. Singletary had ridden his bike and walked the two-wheeler up and down the tented rows until he spotted Wright. He purchased a large acrylic painting from him that hung above his bed.

“I would have to say he was a genius,” said Wright, who often attended the same events as Singletary. “He was very quiet, humble. You wouldn’t even know he was there. Sometimes when he would come to an exhibit or opening, he would walk in or walk around and take a look, and he’d be gone.”

Singletary wrote his obituary and a seven-page booklet detailing his life, research, public presentations and achievements, which were distributed at his funeral on July 12. One snippet about a 2010 visit to the White House with the Martin Luther King Family Life Institute reads, “This was one of the greatest things that Dr. Singletary had done in his life. Although President Barack Hussein Obama was on vacation, it was good to see where our president lives.”

At the top of Tracy’s to-do list is ensuring the museum, which opened in 1980, continues to operate; it will require a curator, as many of the pieces lack origin information. He is unsure if he will find notes among the thousands of paper items that need to be sorted.

Tracy didn’t share his brother's passion for history and music. The veteran, his shaggy beard knotted at his chest, said time and miles separated the brothers. Though they weren’t overly close, Tracy promises, “If I have to move here, I will make sure Richard’s legacy continues.”

He is organizing a GoFundMe and is hopeful of receiving grants and help from local philanthropists.

He’s sad about outliving his younger siblings. His lifelong job was to care for them, he said, which is among the reasons he’s committed to preserving, in Singletary's words, “a well-lived life of gentility, humility, cultural appreciation and service to his fellow human beings.”

“I was not around him all the time, but I knew he was there,” Tracy said. “I will miss him, just his presence.”